In the previous introduction and article on cycles I explained that we need some kind of time delay or timing element to explain the ice age cycles. This is because one of the key problems with explaining the ice-ages is explaining why they tend to occur every 110,000 years (or less ).

This article looks at one potential delay mechanism that could set the time between Ice-ages. In doing so, this article introduces a little discussed phenomenon which is the effect of long-term change of temperature on the earth’s crust. It then introduces a mechanism I called the “Caterpillar effect” which must play a significant part in tectonic plate movement.

See also:

The Theory

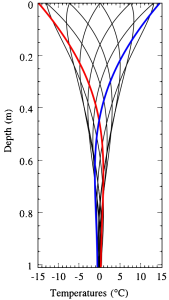

Fig 3.1 Redrawn from Anderson (1998) INSTAARNear-Surface Thermal Profiles in Alpine Bedrock: Implications for the Frost Weathering of Rock

As the surface air of the earth changes in temperature, that change causes a heat flux into or out of the ground causing the earth to tend to cool or warm. The result is as shown to the right which is the daily change in temperature near the surface for a +/- 15C swing. The earth’s surface warms and cools with the changing air temperature. Layers nearest the air change with the change in air temperature, but the affect become reduces with depth as the rock is more insulated from changes at the surface.

Thermal Profile of Soil

Assuming that conduction is the heat transfer mechanism within the bedrock, the relevant thermal problem can be approximated as a 1-d conduction problem with a sinusoidal variation of temperature at the top boundary of a half space (Carslaw and Jaeger, 1959; see also Gold and Lachenbruch, 1973 for applications to permafrost problems). The thermal dependence on time (t) and depth (z) is expected to be

T(z, t) = Tave(z) + [Taexp(-z/z*) cos(ωt – z/z*)]

where T is the mean temperature profile (geotherm), and Ta is the (half) amplitude of the temperature variation at the surface, z = 0. The length scale, z*, for the decay of the amplitude of the signal is dictated by the thermal diffusivity of the material, κ, and the period of the oscillation of the temperature at the boundary, P (= 2π/ω, where ω is the angular frequency):

z* = (κP/π )½

For typical diffusivities of about 1-2 mm2 s-1, this length scale is about 20 cm for a daily cycle, 3 to 4 m for the annual cycle.

Temperature variation with Ice-ages

Based on the figure of diffusivity given by Whittington et al., (2009) of around 2mm2 s-1 a variation of +/-4C above around the average temperature, the variation of temperature with depth for a 112,000 sinusoidal change in surface temperature would be as follows:

As can be seen above in Fig 3.2, the change in crustal temperature is significant up to 4km.

The Creaking earth

As everyone knows, warming causes expansion, so how much will the earth’s crust warm for a 1C change in crustal temperature? Expansion coefficient of most rocks are around 5-10 x10-6 per degree change. Taking the crust as being granite with an temperature expansion coefficient of (8×10-6) the expansion of the crust at the equator of approximately 40,000km due to a 1C change in temperature is approximately:

1.0 x 40,000 x 1000 x 8×10-6 = 320m

For a 100,000 year heating cycle that amounts to:

320/100,000 = 3.2mm/year

However closer to the surface the expansion is much greater as shown by the following graph:

Fig 3.3 estimated expansion tangentially to surface at equator for a +/-4C sinusoidal change in temperature.

How does this compare with the rate of movement of tectonic plates?

Data on the movement of plates is relatively hard to find. Typical figures are:

- It is said the Eurasian Plate is moving away from the North American Plate at a rate about 30 mm per year.(source)

- Relative speed of plates adjoining Pacific plate are:

| Plate | Relative Velocity with Pacific plate (mm/yr) |

|---|---|

| Antarctic | 11.3 |

| Cocos | 2.0 |

| Eurasian | 5.2 |

| Nazca | 13.3 |

Table 3.1 Figures based on the The Physics Factbook

Which suggests plates are moving around 2-30mm/year compared to a maximum thermal expansion of around:

| Depth | Total movement (km) | Relative Velocity (mm/yr) |

|---|---|---|

| Surface | 2.3km | 23 |

| 1.2km | 1.0 | 10 |

| 2.3km | 0.5 | 5.0 |

| 4.7km | 0.1 | 1.0 |

Table 3.2 Movement of earth’s crust around circumference

over 100,000 ice-age cycle

So, whilst the change in size of the crust is very small amounting to only 58PPM at the surface, given the size of the earth, the actual effect at the plate boundaries is huge.

Differential Thermal Expansion

By layer

There is clearly a massive difference over an ice-age cycle between expansion due to temperature change at the surface and even a few kilometres down. This will lead to differential expansion and contraction, both between different layers at different depths and therefore exposed to different temperature changes, but also between rocks with different coefficients of thermal expansion.

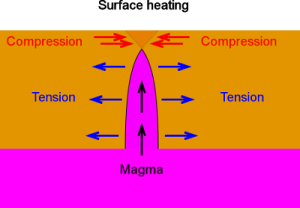

Taking warming first, the increase in temperature at the surface will tend to make rocks there expand and so press outward of adjacent rock resulting in an outward force. This force will reduce the further down we go, until it changes into a tensional force tending to hold the rocks together. As rocks are about ten times stronger under compression than tension, it is possible for a thin layer of surface rock to cause deep cracking beneath the surface. And because the crust effectively floats on the molten magma beneath it, it is possible an intrusion of magma may take the place of the contracting crust (Alternatively, such cracks may be filled by mineralisation) A diagram of rock filling with magma is shown above-right (note: vastly expanded horizontal axis)

At the surface, the rock is compressed via thermal expansion. The diagram shows the crust as having split allowing magma to intrude into the cracks. This magma will then cool reforming a solid crust.

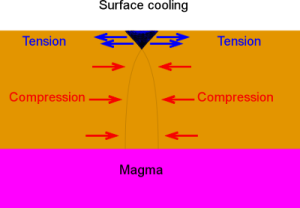

But when the surface then cools, because the intruded magma has had time to solidify as the surface shrinks. This now tends to pull apart the surface opening up cracks as shows to right (note vastly expanded horizontal scale).

However, this time because the compression at depth seals the crust, it stops magma coming to the surface. Deep surface cracks cannot be filled by magma, so instead the crack is unstable and tends to collapse or be filled by water and surface debris. However, whilst the material is different, the effect over several thousand years is to refill the crack with solid material so that when the surface heats again, the cycle repeats.

By material

The other effect is that different rocks will expand and contract at different rates and by different amounts.

| Rock Type | linear-expansion coefficient (in 10−6 per degree Celsius) |

| granite and rhyolite | 8 ± 3 |

| andesite and diorite | 7 ± 2 |

| basalt, gabbro, and diabase | 5.4 ± 1 |

| sandstone | 10 ± 2 |

| limestone | 8 ± 4 |

| marble | 7 ± 2 |

| slate | 9 ± 1 |

Table 3.3 (Encyclopedia Britannica)

Thus, layers such as sandstone will be expanding and contradicting twice as much as basalt. This will lead to bend, twisting and other stresses which eventually may lead to catastrophic re-alignments and earthquakes. Again, the effect of this differential expansion and higher compressive strength of rock will be to tend to cause the highest expanding rocks to push out when heating causing cracking in the rocks with lower thermal expansion. These cracks will then tend to fill – and the cycle repeat.

See also:

High-Resolutio

n Phylogenetic Analysis of Southeastern Europe Traces Major Episodes of Paternal Gene Flow Among Slavic Populations

Lovorka Barać Lauc*, 1 ,

Irena Martinović Klarić*,

Siiri Rootsi†,

Branka Janićijević*,

Igor Rudan‡§,

Rifet Terzić∥,

Ivanka Čolak¶,

Ante Kvesić¶,

Dan Popović*,

Ana Šijački#,

Ibrahim Behluli**,

Dobrivoje Đorđevi憆,

Ljudmila Efremovska††,

Đorđe D. Bajec#,

Branislav D. Stefanović#,

Richard Villems† and

Pavao Rudan*

+ Author Affiliations

*Institute for Anthropological Research, Amruševa 8, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia; †Estonian Biocentre, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia; ‡School of Public Health Andrija Štampar, University of Zagreb Medical School, Zagreb, Croatia; §University of Edinburgh Medical School, Edinburgh, Scotland; ∥Medical Faculty, University of Tuzla, Tuzla, Bosnia and Herzegovina; ¶Clinical Hospital Center “Bijeli Brijeg,” Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina; #Emergency Unit of Clinical Center of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia and Montenegro; **Medical Faculty, University of Prishtina, Prishtina, Kosovo; and ††Medical Faculty, University of Skopje, Skopje, MacedoniaE-mail: mpericic@luka.inantro.hr

Accepted May 30, 2005.

Abstract

The extent and nature of southeastern Europe (SEE) paternal genetic contribution to the European genetic landscape were explored based on a high-resolution Y chromosome analysis involving 681 males from seven populations in the region. Paternal lineages present in SEE were compared with previously published data from 81 western Eurasian populations and 5,017 Y chromosome samples. The finding that five major haplogroups (E3b1, I1b* (xM26), J2, R1a, and R1b) comprise more than 70% of SEE total genetic variation is consistent with the typical European Y chromosome gene pool. However, distribution of major Y chromosomal lineages and estimated expansion signals clarify the specific role of this region in structuring of European, and particularly Slavic, paternal genetic heritage. Contemporary Slavic paternal gene pool, mostly characterized by the predominance of R1a and I1b* (xM26) and scarcity of E3b1 lineages, is a result of two major prehistoric gene flows with opposite directions: the post-Last Glacial Maximum R1a expansion from east to west, the Younger Dryas-Holocene I1b* (xM26) diffusion out of SEE in addition to subsequent R1a and I1b* (xM26) putative gene flows between eastern Europe and SEE, and a rather weak extent of E3b1 diffusion toward regions nowadays occupied by Slavic-speaking populations.

Key words

phylogenetic analysis

Y chromosomal binary haplogroups

southeastern Europe (SEE)

Introduction

Southeastern Europe (SEE) has traditionally been viewed as a “bridge” (Childe 1958) between the Near East and temperate Europe or as a key area in the process of transition from hunter-gathering to agropastoral, farming societies in Europe (e.g., Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza 1984; Renfrew 1987; Zvelebil and Lillie 2000). Recent phylogeographic analyses of Y chromosome E and J haplogroups indicate that southern Europe and the Balkans indeed could have been both the receptors and sources of gene flow during and after the Neolithic (Cruciani et al. 2004; Semino et al. 2004). The STR haplotype diversity of these two haplogroups is considerably younger than that of other Y chromosome haplogroups spread in Europe. Among the latter, haplogroup I, perhaps, most clearly represents the paternal genetic component of the pre-Neolithic Europeans. In contrast to E and J, haplogroup I is virtually absent in Middle East and West Asia (Semino et al. 2000), and two of its major subclades have frequency peaks in northern Balkans and Scandinavia (Rootsi et al. 2004). Semino et al. (2000) and Barać et al. (2003) hypothesized that, besides southwest Europe, the northern Balkans could have been another possible Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) refugium and a reservoir of M170.

In this study we first examined the extent and nature of SEE paternal genetic contribution to the European genetic landscape based on a high-resolution Y chromosome typing involving 681 unrelated males from four modern states, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia and Montenegro (including the province of Kosovo), and Macedonia (fig. 1). Second, we exploited available data on Y chromosome variation among different southern, western, and eastern Slavic-speaking populations in Europe to draw conclusions about possible origin of major paternal lineages in the Slavic gene pool. Finally, based on geography, we assessed patterns of Y chromosome diversity across SEE.

Materials and Methods

We analyzed 681 males from seven populations from SEE and 5,017 Y chromosomes from 81 western Eurasian populations available from literature. Blood samples were collected from healthy unrelated adults after obtaining informed consent. DNA was extracted using the salting-out procedure (Miller, Dykes, and Polesky 1988).

The following set of biallelic markers was analyzed using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) or in/del assays according to published protocols: M9 (Whitfield, Sulston, and Goodfellow 1995), YAP (Hammer and Horai 1995), SRY-1523 (Whitfield, Sulston, and Goodfellow 1995) (SRY-1523 is equivalent to SRY10831 [Whitfield, Sulston, and Goodfellow 1995]), 92R7 (Mathias, Bayés, and Tyler-Smith 1994), 12f2 (Rosser et al. 2000), M170, M173, M89 (Underhill et al. 2000), and P37 (Y Chromosome Consortium 2002). The polymorphic single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) underlying markers M26, M35, M67, M69, M78, M81, M82, M92, M102, M123, M172, M201 (Underhill et al. 2000), M223 (Underhill et al. 2001), M241, M242, M253 (Cinnioğlu et al. 2004), and SRY8299/4064 (Whitfield, Sulston, and Goodfellow 1995) were sequenced after polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. PCR-amplified products were purified using shrimp alkaline phosphatase and exonuclease treatment following Kaessmann et al. (1999) and sequenced using the BigDye Terminator Version 3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) on an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) by using the DNA Sequencing Analysis Software Version 3.7 (Applied Biosystems). M9 was typed on all samples, and other markers were typed hierarchically according to their known phylogeny. A tentative assignment of all R1 chromosomes derived at M173 but without the G to A back mutation at SRY10831 into haplogroup R1b was based on the observations of Cruciani et al. (2002). Phylogenetic relationships of analyzed biallelic markers are presented in figure 2. Mutation labeling follows the Y Chromosome Consortium (2002).

Y chromosomal SNP tree and haplogroup frequencies (percent) in seven SEE populations. *Croatian mainland from Barać et al. (2003) was additionally genotyped for deeper resolution of I in Rootsi et al. (2004) and for E and J in the present study. E3b1α chromosomes were defined by A7.1 nine-repeat allele.

In addition, we surveyed eight short tandem repeats (STRs) DYS19, DYS385, DYS389I, DYS389II, DYS390, DYS391, DYS392, and DYS393 (Kayser et al. 1997) on all 681 SEE chromosomes and one additional GATA STR A7.1 (DYS460) (White et al. 1999) in E3b1-M78 chromosomes. PCR products were detected on an ABI PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), and fragment sizes were analyzed by the GeneScan Analysis Software Version 3.7 (Applied Biosystems).

Expansion ranges were expressed as the age of STR variation estimated as the average squared difference in the number of repeats of seven STRs (DYS19, DYS389I, DYS389II, DYS390, DYS391, DYS392, and DYS393) between all sampled chromosomes and the founder haplotype divided by w (effective mutation rate of 0.00069 per locus per 25 years) (Zhivotovsky et al. 2004). Phylogenetic networks were obtained by using the same seven STRs as those used for expansion range estimates. The phylogenetic relationships between microsatellite haplotypes were determined by using the program NETWORK 4.0b (Fluxus Engineering). Networks were calculated by the median-joining method (Bandelt, Forster, and Röhl 1999), and STR loci were weighted according to Helgason et al. (2000). Haplogroup-frequency and haplogroup-variance surfaces were reconstructed following the Kringing procedure by use of the Surfer System (Golden Software), the frequency data reported in table 1 and variance data from this study and literature, as specified in figures 3–7. Credible regions (95% CRs) for haplogroup frequencies were calculated from posterior distribution of the proportion of the group of lineages in the population, as in Richards et al. (2000). For the purpose of correlating Y chromosomal frequencies with geography, we used Spearman’s bivariate correlation procedure (SPSS for Windows, 7.5.1.). Sampled individuals were pooled into 12 regional towns (fig. 1) with following latitude (N) and longitude (E) values: (1) 46°02′, 15°90′; (2) 45°82′, 15°98′; (3) 45°77′, 18°17′; (4) 45°40′, 14°80′; (5) 45°23′, 13°93′; (6) 42°65′, 18°09′; (7) 44°22′, 17°90′; (8) 43°35′, 17°80′; (9) 43°39′, 17°55′; (10) 44°82′, 20°46′; (11) 42°67′, 21°17′; and (12) 41°98′, 21°43′.

Summarized Percent Frequencies of R1b, R1a, I1b* (xM26), E3b1 and J2e

I1b* (xM26) frequency and variance surfaces in SEE (panels A and B) were generated from the data in this study. I1b* (xM26) frequency surfaces in Europe, northern Africa, and Asia Minor (panel C) were generated from the data reported in table 1, and variance surfaces (panel D) were generated from STR data in this study and Rootsi et al. (2004).

E3b1 frequency and variance surfaces in SEE (panels A and B) were generated from the data in this study. E3b1 frequency surfaces in Europe, northern Africa, and Asia Minor (panel C) were generated from the data reported in table 1, and variance surfaces (panel D) were calculated from STR data in this study and Semino et al. (2004).

R1a frequency and variance surfaces in SEE (panels A and B) were generated from the data in this study. R1a frequency surfaces in Europe, northern Africa, and Asia Minor (panel C) were generated from the data reported in table 1, and variance surfaces (panel D) were calculated from STR data in this study, Rootsi et al. unpublished data, Cinnioğlu et al. (2004), Behar et al. (2003), Weale et al. (2002), Wilson et al. (2001), Helgason et al. (2000), and Hurles et al. (1999). Shaded areas in panel D correspond to regions for which combined SNP and STR Y chromosomal data are not available.

R1b frequency and variance surfaces in SEE (panels A and B) were generated from the data in this study. R1b frequency surfaces in Europe, northern Africa, and Asia Minor (panel C) were generated from the data reported in table 1, and variance surfaces (panel D) were calculated from STR data in this study, Rootsi et al. unpublished data, Cinnioğlu et al. (2004), Behar et al. (2003), Weale et al. (2002), Wilson et al. (2001), Helgason et al. (2000), and Hurles et al. (1999). Shaded areas in panel D correspond to regions for which combined SNP and STR Y chromosomal data are not available.

J2e frequency and variance surfaces in SEE (panels A and B) were generated from the data in this study. J2e frequency surfaces in Europe, northern Africa, and Asia Minor (panel C) were generated from the data reported in table 1, and variance surfaces (panel D) were generated from STR data in this study and Semino et al. (2004).

Results and Discussion

One-third of the studied SEE Y chromosomes has the derived P37 C allele and is classified to haplogroup I1b* (xM26) (fig. 2). A detailed survey demonstrates that I1b* (xM26) lineages reach maximum frequency in SEE (fig. 3C) and that I1b* (xM26) STR variance peaks over a large geographic region encompassing both southeastern and central Europe (fig. 3D). I1b* (xM26) frequency peaks in Herzegovinians (64%) and Bosnians (52%) while preserving substantial (30%) frequencies in all SEE populations with the exception of two reproductively isolated and non-slavic speaking populations, Kosovar Albanians and Macedonian Romani (fig. 3A). The incidence of I1b* (xM26) decreases from SEE toward western (from 20% in Slovenians abruptly to 1% in northern Italians) and southern (17%–18% in Albanians and northern Greeks, 8% in southern Greeks, 2% in Turks) and retains frequencies of 7%–22% in central and eastern Europe (table 1). The highest STR variance of I1b* (xM26) lineages (0.34 to 0.23) is in Bosnians, Czechs and Slovaks, Hungarians, Herzegovinians, and Serbians (fig. 3B and D). In both cases, when all studied SEE populations are considered together and upon exclusion of Kosovar Albanians and Macedonian Romani, I1b* (xM26) frequency and variance do not show significant correlations with geography (table 2). Moreover, I1b* (xM26) phylogenetic network (fig. 8A) shows high haplotype diversity and sharing of founder haplotype among investigated populations. In fact, homogenous distribution of elevated frequency accompanied with high diversity of I1b* (xM26) lineages among different SEE populations may be viewed as a genetic signature of their common paternal history over a long period of time. Rootsi et al. (2004) estimated that I1b* (xM26) diverged from I* at 10.7 ± 4.8 kilo years ago (KYA), possibly relating to the post–Younger Dryas (YD) climate amelioration in Europe, and that I1b* (xM26) expansion occurred around the early Holocene at 7.6 ± 2.7 KYA. Considering only our SEE sample, the coalescent estimate of I1b* (xM26) is substantially older (11.1 ± 4.8 KYA). This finding suggests that the I1b* (xM26) lineages might have expanded from SEE to central, eastern, and southern Europe, presumably not earlier than the YD to Holocene transition and not later than the early Neolithic.

Correlations of Major Y Chromosome Haplogroup Frequencies and Variances with Geography

Microsatellite networks of major Y chromosomal lineages in SEE: (A) I1b* (xM26) (B) E3b1α; (C) R1a. Microsatellite haplotypes are represented by circles, with areas proportional to the number of individuals harboring the haplotype. Smallest circle represents single haplotype in panel B and C and two haplotypes in panel A. Branch lengths are proportional to the number of one-step mutations separating two haplotypes.

Haplogroup E3b1-M78 is the second most prevailing one (23%) in the studied sample with E3b1-M78 chromosomes accounting for almost all E representatives (98%) except a single E3b2-M81 and two E3b3-M123 chromosomes (fig. 2). E3b1-M78 is the most common haplogroup E lineage in Europe (Cruciani et al. 2004; Semino et al. 2004). The spatial pattern shown in figure 4(C) depicts a nonuniform E3b1 geographic distribution with a frequency peak centered in south Europe and SEE (13%–16% in southern Italians and 17%–27% in the Balkans). Declining frequencies are evident toward western (10% in northern and central Italians), central, and eastern Europe (from 4% to 10% in Polish, Russians, mainland Croatians, Ukrainians, Hungarians, Herzegovinians, and Bosnians). Noteworthy is a low E3b1 frequency (5%) in Turkey. Apart from its presence in Europe and the Middle East, E3b1 is also found in eastern and northern Africa. Cruciani et al. (2004) estimated that E3b-M78 might have originated in eastern Africa about 23.2 KYA (95% confidence interval [CI] 21.1–25.4). Although present level of phylogenetic resolution does not allow further subdivision of this haplogroup by binary markers, based on strong geographic structuring of diverse microsatellite motifs, E3b-M78 is suggested to be a collection of subclades with different evolutionary histories (Cruciani et al. 2004; Semino et al. 2004) out of which the α cluster, largely characterized by an A7.1 nine-repeat allele, is confined to Europe (the Balkans) and Turkey (Cruciani et al. 2004). E3b1 variance distribution depicted in figure 4(D) does not overlap with its frequency distribution possibly because analyzed E3b1 chromosomes harbor diverse background motifs. It is very likely that a variance peak centered in northeastern Africa as well as high variance values in Turkey and southern Italy are due to the inclusion of δ (and a few southern Italian β) chromosomes. Almost 93% of SEE E3b1 chromosomes are classified into α cluster. In Europe, the highest E3b1α variance is among Apulians, Greeks, and Macedonians, and the highest frequency of the cluster is among Albanians, Macedonians, and Greeks (table 1). Bearing in mind the congruent E3b1α frequency, variance maximums, and star-like phylogenetic network (fig. 8B), it is possible to envision that a yet undefined sublineage downstream of M78, characterized by the nine-repeat allele at A7.1 locus, may have originated in south Europe and SEE from where it dispersed in different directions. Furthermore, it may be envisioned that the observed E3b1α frequency distribution in Anatolia might stem from a back migration originating in south Europe and SEE. Our estimated range expansion of 7.3 ± 2.8 KYA is close to the 7.8 KYA (95% CI 6.3–9.2 KYA) estimate for expansions of cluster α chromosomes in Europe reported by Cruciani et al. (2004) and the 6.4 KYA estimate for E3b1-M78 STR variance in Anatolia dated by Cinnioğlu et al. (2004). The frequency and variance decline of E3b1 in SEE is rather continuous (fig. 4A and B), with a frequency peak extending from the southeastern edge of the region and a variance peak in southwest. Observed high E3b1 frequency in Kosovar Albanians (46%) and Macedonian Romani (30%) represent a focal rather than a clinal phenomenon resulting most likely from genetic drift. E3b1 frequency and variance are significantly correlated with latitude, showing higher values toward south (table 2), both when all SEE populations are considered (r = −0.51, P = 0.05, for frequency and r = −0.706, P = 0.05, for variance) and when Kosovar Albanians and Macedonian Romani are excluded (r = −0.597, P = 0.05, for frequency and r = −0.676, P = 0.05, for variance). A lower frequency of E3b1 significantly distinguishes populations of the Adriatic-Dinaric complex, i.e., mainland Croatians, Bosnians, and Herzegovinians (7.9%; 95% CI 0.054–0.114), from their neighboring populations of the Vardar-Morava-Danube river system, i.e., Serbians and Macedonians (21.9%; 95% CI 0.166–0.283). These observations hint a mosaic of different E3b1 dispersal modes over a short geographic distance and point to the Vardar-Morava-Danube river system as one of major routes for E3b1, in fact E3b1α, expansion from south and southeastern to continental Europe. In fact, dispersals of farmers throughout the Vardar-Morava-Danube catchments basin are also evidenced in the archaeological record (Tringham 2000).

R1a haplogroup occurs at 16% frequency in SEE (fig. 2). The age of M17 has been approximated to 15 KYA (Semino et al. 2000; Wells et al. 2001). Kivisild et al. (2003) suggested that southern and western Asia might be the source of R1 and R1a differentiation. Current R1a-M17/SRY-1532 distribution in Europe shows an increasing west-east frequency and variance gradients with peaks among Finno-Ugric and Slavic speakers (fig. 5C and D). Similar to I1b* (xM26), R1a frequency gradient decreases slowly to the south (to 10% in Albanians, 8% in Greeks, and 7% in Turks) and abruptly in the west (3% in Italians) (table 1). R1a frequency and STR variance decrease in the north-south direction in SEE, from 34%–25% in mainland Croatians and Bosnians to 12%–16% in Herzegovinians, Macedonians, and Serbians (fig. 5A and B). Moreover, R1a frequency is significantly correlated with latitude (table 2) when all studied SEE populations are considered (r = 0.865, P = 0.01) and also when Kosovar Albanians and Macedonian Romani are excluded (r = 0.743, P = 0.01). High R1a haplotype diversity in SEE is evident in the phylogenetic network (fig. 8C) and the estimated range expansion at 15.8 ± 2.1 KYA, consistent with its deep Paleolithic time depth, as previously suggested (Semino et al. 2000; Wells et al. 2001). At this level of resolution, it is not clear what temporal and effective population size differences contributed to this deep Paleolithic signal as high R1a variance in SEE might be explained by either ancient demography or more recent bottlenecks and founder effects in different Slavic tribes. At least three major episodes of gene flow might have enhanced R1a variance in the region: early post-LGM recolonizations expanding from the refugium in Ukraine, migrations from northern Pontic steppe between 3000 and 1000 B.C., as well as possibly massive Slavic migration from A.D. 5th to 7th centuries.

R1b haplogroup is present in SEE at a level of 9% (fig. 2). R1b-M173 lineages are considered to trace an Upper Paleolithic migration from West Asia to European regions then occupied by Aurignacian culture (Semino et al. 2000; Underhill et al. 2001; Wells et al. 2001). The spatial distribution of R1b lineages shows a frequency peak (40%–80%) in western Europe and a decrease in eastern (with the exception of 43% in the Ossetians) and southern Europe (fig. 6C), whereas R1b variance shows multiple peaks in West Europe and Asia Minor (fig. 6D). While R1b variance displays a clear-cut northwestern-southeastern decline in SEE (fig. 6B), R1b frequency decline continues from western toward southeastern and southern Europe, but two intermediate local peaks are evident, in north among mainland Croatians and Serbians and in south among Kosovar Albanians, Albanians, and Greeks (fig. 6C). These spatial patterns might be due to the fact that R1b lineages contain associated RFLP 49a,f ht 15 and 35 sublineages with opposite distributions possibly reflecting repeopling of Europe from Iberia and Asia Minor during the Late Upper Paleolithic and Holocene (Cinnioğlu et al. 2004). The overall R1b frequency distribution in the Balkan Peninsula suggests its possible arrival from two different source populations during recolonization of Europe. We estimated the range expansion of R1b lineages in SEE at 11.6 ± 1.4 KYA. Although R1b lineages could have accumulated STR variance before diffusion in SEE, it is significant that its estimated range expansion almost perfectly matches the coalescent estimate for the I1b* (xM26) lineages, pointing to the YD to Holocene transition as possibly a period when these two major Y chromosome lineages started to expand in the region.

Haplogroup J defined by a 12f2 polymorphism is subdivided into two major clades, J1-M267 and J2-M172 (Cinnioğlu et al. 2004). J2-M172 is more prevalent in Europe where at least five different lineages can be traced—J2e*-M102, J2e1-M241, J2*-M172, J2f*-M67, and J2f1-M92 (fig. 2, Semino et al. 2004). In SEE, the most frequent are J2e lineages that comprise 5% of all chromosomes, while J2f cluster, a predominant J2 cluster in Greeks and Italians (Di Giacomo et al. 2004), is present at a frequency less than 1% (fig. 2). Most likely due to genetic drift, Kosovar Albanians harbor a J2e frequency peak whereas variance maximum declines from the southeastern edge of the studied region (fig. 7A and B). Even though J2e frequencies do not correlate with geography, J2e variances show significant correlations with latitude and longitude and are highest toward south and east of the region (table 2). The correlation between geography and haplogroup frequencies are significant when all SEE populations are considered (r = −0.949, P = 0.05) and when Kosovar Albanians and Macedonian Romani are excluded (r = −0.949, P =0.05). Our estimated range expansion for J2e at 2.8 ±1.6 KYA (for all SEE populations) and 3 ± 1.9 KYA (SEE populations without Kosovar Albanians) succeeds the dates of 7.9 ± 2.3 KYA (Semino et al. 2004) and 8.6 KYA (Cinnioğlu et al. 2004). The J2e-M102 spatial distribution depicted in figure 7(C and D) with two frequency and variance peaks positioned in the Balkans and central Italy may be explained by the maritime spread of J2e lineages from southern Balkans toward Apennines at times later than those based on the classical model of demic expansions carried by Neolithic agriculturists from the Middle East via Balkans toward rest of Europe.

Widely spread Romani haplogroup H1 is a major lineage cluster in Macedonian Romani (fig. 2). A 2-bp deletion at M82 locus defining this haplogroup was also reported in one-third of males from traditional Romani populations living in Bulgaria, Spain, and Lithuania (Gresham et al. 2001). Its ancestral M52 A → C transversion was reported in the Vlax Roma (Kalaydjieva et al. 2001) and India (Ramana et al. 2001; Wells et al. 2001; Kivisild et al. 2003). Out of 34 H1-M82 males, 10 were typed for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and belonged to haplogroup M that was highly frequent in Macedonian Romani (Cvjetan et al. 2004), traditional Romani populations (Gresham et al. 2001), and India (Kivisild et al. 2003). High prevalence of Asian-specific Y chromosome haplogroup H1 and mtDNA haplogroup M supports their Asian (Indian) origin and a hypothesis of a small number of founders diverging from a single ethnic group in India (Gresham et al. 2001).

F*, G-M201, K* (xP), P* (xR1, Q), and Q-M242 lineages occur at low frequencies in SEE (fig. 2). The Herzegovinian Q-M242 sample harbors a STR motif previously seen in eastern Adriatic haplogroup Q lineages that are marked by the typical presence of the unusually long DYS392-15 allele (Barać et al. 2003).

We conclude that even though the majority of identified SEE paternal lineages are consistent with the typical European Y chromosome gene pool, their distribution and estimated range expansions clarify the specific role of this region in structuring the European genetic landscape. Contemporary Slavic paternal gene pool is characterized by the predominance of R1a and I1b* (xM26) variants as well as the scarcity of E3b1 lineages as a result of the following prehistoric gene flows. First, we envision the post-LGM R1a expansion from eastern to western Europe and second the YD-Holocene I1b* (xM26) diffusion out of the Balkans in addition to subsequent R1a and I1b* (xM26) putative gene flows between eastern Europe and SEE. Lastly, we envision a weaker extent of E3b1 dispersal out of southern Europe and SEE toward eastern Europe rather than toward western (especially Mediterranean) Europe. Our results also stress that I1b* (xM26) wide geographic distribution and massive frequencies accompanied with high diversity in most of its range among major SEE populations testify impressively to their common paternal history, whereas observed genetic heterogeneity structured mostly along the northwestern-southeastern axis is a result of attested prehistoric and historical gene flows with different temporal and directional characteristics. Yet the main difference between the paternal genetic history of the Slavic-speaking populations lies in the presence, among eastern Slavs (Russians, Ukrainians, Belarussians), of haplogroup N chromosomes, virtually absent among any of the western or southern Slavic populations (Rosser et al. 2000; Semino et al. 2000; Barać et al. 2003; Tambets et al. 2004), unequivocally suggesting that the historic eastward expansion of Slavs in the middle of the first millennium A.D. resulted in a substantial admixture of them with the substratum populations, inhabiting East Europe, among whom this largely northern Eurasian haplogroup was and still is widely spread.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the donors for their kind participation in this study. Special thanks go to Toomas Kivisild for friendly guidance and helpful comments for this manuscript. We wish to express our gratitude to two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. This research was supported by the Ministry of Science, Education and Sports of the Republic of Croatia grant for project 0196005 (to P.R.), Estonian basic research grant 514 (to R.V.), European Commission Directorate General Research grant ICA1CT20070006 (to R.V.), and Estonian Science Foundation grant number 6040 to Kristiina Tambets.

Footnotes

↵1 The first two authors contributed equally to this study.

Lisa Matisoo-Smith, Associate Editor

References

Articles citing this article

My impression is that variations in heat flow from the centre of earth and the effects of isostasy with loading/unloading of ice would far outweigh any effects on the crust from atmospheric temperature changes. Wikipedia have an explanatory page at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Post-glacial_rebound

Doesn’t that raise the intriguing possibility that ice-ages are caused by variations in heat from the crust?

And thanks for the suggestion regarding ice loading. I wasn’t very happy with the use of CO2 as a feedback mechanism leading to a cyclic behaviour and it hadn’t occurred to me that there was a more obvious change due to temperature as huge lumps of ice begin compressing the surface around the poles.

I’m going to have to think about it.

Scottish Sceptic says: 25th March 2011 at 10:26 am (something fishy with the timestamp of the replies)

“Doesn’t that raise the intriguing possibility that ice-ages are caused by variations in heat from the crust?”

To me it is obvious that the current cycle of glacials / interglacials is made possible by the temperature of the deep oceans dropping below a certain value.

(ice ages are the cold periods earth experiences every 150 – 180 million years or so)

I’m pretty confident that the temperature of the DEEP oceans is caused by geothermal heat, starting at the time of their creation. Since then they have been kept warm by the low geothermal flux (100mW/m^2 or so) plus all other forms of geothermal heat escaping into the oceans.

Compare this to how a thermos flask works. Once you have heated a fluid and put it into a thermos flask, it takes very little energy to MAINTAIN the high temperature.

Same for the oceans. They were created very hot, are heated from below, and almost the entire solar heated surface is acting as a barrier, preventing the bottom warmed water to reach the surface. Only at high latitudes can the deep ocean shed some energy.

Our atmosphere does not warm the surface. It should be obvious that it is the other way around, as classical meteorology has always assumed.

So the reason why the surface temperature on earth is some 90K higher than on the moon is mostly the pre-heated oceans. The atmosphere only reduces the energy loss to space some.

see https://tallbloke.wordpress.com/2014/03/03/ben-wouters-influence-of-geothermal-heat-on-past-and-present-climate/

It did occur to me that in periods when very carbon rich rock is being subducted, then you would get a very different emissions than when carbon poor rock. Similarly with sulphur and other elements.

Changes in geothermal heat coming to the surface are an intriguing idea, but from memory the geothermal flux is only about 1.7W/m-2 so there would need to be a massive increase.

It might be easier for hydrothermal – because if you could get enough flow, this could effectively bypass much of the thermal insulation of the crust.

You miss my point. The geothermal FLUX through the crust is very low.

~100 mW/m^2 for oceanic and ~65 mW/m^2 for continental crust.

The flux at continents can be neglected since it warms the same soil as the sun does and can’t compete with the average 240 W/m^2 solar.

In the oceans the story is completely different.

Firstly, they have been very hot (steam, boiling) in their early existence.

Presently they are ~275K, already 20K above the infamous 255K effective temperature. More relevant almost 80K above the average moon surface temperature.

The sun warms only the upper 100 meters or so of the oceans. Below the thermocline NO more solar influence noticed. All solar energy leaves the oceans at the surface and then via the atmosphere to space.

This warm surface layer makes it impossible for geothermally heated water to reach the surface, unless of course it is warmer than the surface water.

The 100 mW/m^2 flux is enough to warm the average water column 1K every ~5000 years.

In the linked text I show large magma eruptions totalling some 136 million cubic KILOMETER. (covers the USA plus Canada under almost 7 km magma) Enough to potentially warm the oceans more than 20K.

Since these eruptions stopped, the deep oceans have been cooling down, some 18K until present. About 3 million years ago they were cold enough to allow the start of the current glacial / interglacial cycle.

With ice covering the high latitude oceans during a glacial, there is no place anymore where the DEEP oceans can loose energy, so they warm up very slowly, until they are warm enough to thaw the ice from below.

Whilst it is largely true, I don’t totally agree that the lower colder layers can’t come to the surface as there are frequent mentions of “upwelling cold currents”. However whilst these are the exception, over time the effect must be huge.

I hadn’t considered the direct effect of volcanic eruptions. In the next article I suggest ice-age triggered expansion and contraction would lead to volcanic eruptions. And perhaps I ought to think about how much energy is released in this process?

After all, if 2.3km of crust gets subducted, then 2.3km of rock has to be erupted with all the potential heating that could cause.

Scottish-Sceptic says: 6th February 2015 at 1:42 pm

“And perhaps I ought to think about how much energy is released in this process?”

To me energy is the key in the whole climate discussion. Incoming solar radiation is ‘thermalized’ when it hits soil or water.

A full day of sunshine in the tropics warms the upper 100 meter of the oceans ~0,05K.

Same with geothermal heat. You have to consider how much magma is entering the ocean, and what the heating effect is, given the temperature difference and the high heat capacity of water.

Large eruptions like the Ontong Java event have the potential to warm the worlds oceans considerably.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontong_Java_Plateau

Subduction of oceanic crust seams part of a recycling mechanism.

see eg http://www.livescience.com/784-giant-slab-earth-crust-core.html

Ben, once read a well thought out post of deep ocean heating and cooling over glacial periods. The author (sorry cannot find it again) had the idea that during the long frozen time, the Arctic Ocean ice was like a lid on a simmering pot. The low heating rate you mention would slowly heat the low depths and the ice lid would prevent losses. Low geothermal flux would indeed raise the deep water.

DD More says: 5th February 2015 at 11:08 pm

With the setup I gave it is pretty simple to explain the surface temperatures on earth.

The sun raises the temperature of the surface layer of the oceans some 15K above the deep ocean temperature, and the atmosphere slightly reduces the energy loss to space so an energy balance exists.

Trick is that the deep oceans have been heated and are kept warm by geothermal heat.

In my setup the atmosphere does not have to warm the surface, so no greenhouse effect exists.

Climate sensitivity for CO2 is ~0K, probably slightly negative.

Glacials / interglacials can be explained as well with this setup.

No role for CO2 other than plant food.

Pingback: Toward a new theory of ice-ages VIII (How CO2 could control climate) | Scottish Sceptic

I am pretty sure the calculated thermal expansion/contraction of crustal rock is not correct. The three deepest South Apfrican gold mines have now reached depths of 3.5-3.9km. The working rock faces are about 60C. This heat is coming from below. You may be able to find records of the temperature gradient and where the geothermal influence stops and the surface influence starts.

Expansion contraction does not change mass, only mass density. So the overlying weight on faults and vents does not change.

Most earthquakes (almost all) originate in much deeper fault zones. I am quite certain, since this is one reason the US ‘fracking causes earthquakes’ complaint is just wrong. Example is in my last book. Ditto volcanoes. Almost all that geological activity arises from plate tectonics. And there is no periodicy in tectonic crustal movement. This is best shown by the magnetic pole reversals recorded in the spreading basalts of the Mid Atlantic rift. The pole reversals are fairly periodic, and there is no evidence of some cyclic change in the rate of rift spreading. Anyway way too slow to explain either of the Pleistocene ice age beat frequencies.

Rud, obviously the geothermal heat flow creates a temperature gradient which I’ve ignored for simplicity. The effect would be to cause rocks further down to be permanently expanded compared to surface rocks. But after many earth movement they will be in long-term equilibrium – except for induced heating/cooling from the surface.

On the point about the depth of the earthquakes. There are shallower earthquakes. It may be that 10,000 years after the end of the last ice-age, the surface rock is now largely in equilibrium and so the initial movement may have ceased. However, you are also right that the depth of the earthquakes isn’t easily explained.

On the point about periodicity, just as I came to print research came out showing good correlation between oceanic plate thickness and ice-age cycles. So, clearly there is rock movement associated with the ice-age. I think the reason this has only just come to light is because the ice-age cycle (40-100k) is very short compared to the periodic change in magnetic pole (millions) and so you need very sensitive techniques to pick it up.

Pingback: Toward a new theory of ice-ages VII (hitting the buffers) | Scottish Sceptic

Pingback: The Caterpillar theory of tectonic plate movement – it’s just simple physics. | Scottish Sceptic

Pingback: 5 minute experiment shows IR heats water from above | Scottish Sceptic

Pingback: The 30min experiment that proves water heats from the top | Scottish Sceptic

Pingback: Toward a new theory of ice-ages XIV (Putting it all together) | Scottish Sceptic

Scottish Skeptic,

You are completely wrong about the source of heating even in the deep ocean water. We were able to show in our 1989 paper that the heat to warm the Antarctic Bottom Water (from about -1.8 deg C to near 0 deg C as it travels northward ) comes mostly from mixing from above. This is because the eddy diffusivity of mixing oceans is high compared to the molecular conduction from the Earth below. We found that more than two thirds of the warming of the Antarctic Bottom Water as it moved from the Antarctic to the Equatorial region and northward was due to mixing from above that eventually came from the warm atmosphere (due to solar heating). Note that the conduction from below is about 70mW/M2 and mixing in the deep water masses can easily be more than twice that even at 4Km deep water (note the use of milliwatts/m2, not Watt per m2. Fluxes near the surface of the Earth are hundreds of Watts.m2, not mW/m2). You are as confused as most geologists in this matter.

Also, were you able to show that our mechanism of plate tectonics (“On the Forces of Plate Tectonics”) is wrong. It is similar in some ways to your catterpillar effect because both use the concept of expansion and contraction of the Earth’s crust. Our mechanism applies only to the ridges in the oceans and yours is worldwide. I ask your readers to read about our mechanism on the website tectonicforces.org. I hope that your comments are more scientific than your comment that we will not make much progress by criticizing those who back the conventional wisdom of convection and plumes as the cause of plate motion. We showed that convection and plumes cannot be the cause of plate motion and being polite about that is of no help. Science should not be the product of what a scientist believes. Scientists should use the idea of Baconian exclusion or scientific method of Bacon as discussed by Platt in 1964.

Hope to hear from some of you friends. Unfortunately, belief is stronger than rigorous science and that is why progress is so slow.

Jon T. Scott (tectonicforces.org)

Have you commented on the right article? This article isn’t about the source of heat but conductivity through the earth. What it is saying is that changes at the surface take a long time to affect lower layers of the mantle.

All this particular article is saying is that expansion within the crust lags by a considerable time. This is a necessary precondition for this thermal expansion to be part of a cycle. It doesn’t say anything about how or where the warming comes from.