In logic, there is a requirement the world is structured such that A->B which can be read “if A then B”, but is often assumed to mean: “A causes B”.

As a physicist, I was indeed taught that the whole world could be dissected into smaller and smaller constituent parts and that these could all be put together again and their behaviour explained by a set of causal relationships (aka science) to build the world we have. As such the implied philosophical basis of science is that …

“everything has a cause”.

I would now like to suggest that there exists systems where it is not only impractical to describe them as having a cause, but that there is literally no “cause”.

Fortunately for me, after doing physics at University, I went into engineering and fairly quickly the arrogance instilled in me from my school and university courses began to disappear. I realised that in real life, the assumption the world could be dissected into constituent parts and that by knowing “science” you could predict how these would work was false.

Like most people who follow a similar path, I quickly learnt the idea that :

“it might work in theory – but does it work in practice”.

Looking back now, I now have a much higher regard for this engineering philosphy as I now see that this is undoubtedly the origin of what later came to be known as “the scientific method”. AKA (it might look OK in theory – but does it work in practice?)

The “Scientific Method is Anti-Science”

But have you noticed how academics particularly those working in climate really dislike this requirement that theory must be tested in practice. The problem is that science teaches the arrogant assertion that the whole universe can be understood using scientific theory – which being “science” is “settled science” aka “omnipotent” and so never wrong.

But, if science is never wrong, why is there any need to test the theory in practice?

We sceptics see this attitude almost daily. Climate extremists are constantly attacking the “sense check” of comparing the forecasts with what actually happens. Just check any wikipedia page on climate, and if you find a single one where a forecast is compared with what actually happens, have a virtual gold star. Because being written by climate academics, who are at the extreme end of “only theory matters”, in academia, they almost never check whether their theories work by comparing the forecast to what actually happens (or if they do they keep really quiet about it!)

So it seems there is a scale of acceptance of the “Scientific method/”works in practice” philosophy:

At one extreme we have the engineers for whom the “scientific method” aka “it’s got to work in practice” is no key to the way they work that you couldn’t be an engineer if you didn’t check things worked in practice. Then we have the “hard sciences” like physics and chemistry, for whom experimental verification is the bedrock of their subject. They have very little problem with “it must work in practice”, however they also like to have their theories. Then we get to subjects like astronomy. Like engineering, these use the hard science, but unlike engineering, there’s not a lot of experimentation. You cannot for example run a controlled experiment over several billion years of planetary evolution! However, they do still accept the idea that where possible theory should be tested – even if practically it is impossible.

At one extreme we have the engineers for whom the “scientific method” aka “it’s got to work in practice” is no key to the way they work that you couldn’t be an engineer if you didn’t check things worked in practice. Then we have the “hard sciences” like physics and chemistry, for whom experimental verification is the bedrock of their subject. They have very little problem with “it must work in practice”, however they also like to have their theories. Then we get to subjects like astronomy. Like engineering, these use the hard science, but unlike engineering, there’s not a lot of experimentation. You cannot for example run a controlled experiment over several billion years of planetary evolution! However, they do still accept the idea that where possible theory should be tested – even if practically it is impossible.

Then we have climatology. I’ve never seen any climate academic accept their work should be tested. Indeed it is my experience that they attack anyone who dares suggest their theories need testing or that they aren’t omnipotent gods or that “97% consensus” doesn’t prove them right.

Even Sceptic scientists will be seeing red

By this point many people trained in “science” will be seeing red. I understand! I had just the same kind of attitude when I came out of University – and there’s no reason to suppose I wouldn’t still have that attitude if I’d stayed in science.

The reason they will be seeing red, is because the above suggests that those who most accept the need for the so called “scientific method” indeed, are not scientists at all.

Why so many scientists reject the “scientific” method

And this, I suggest is why so many people in science so strongly object to the scientific method – because it isn’t really part of science at all. The root of science was really gentlemen (often clerics who are free most of the week) doing things like collecting flowers as a hobby as part of “seeing god’s great work on earth”. Some then started collecting fossils and other esoteric things. And so the focus of this “knowledge” (from Latin scientia “knowledge” probably in turn from “scindere “to cut divide”) was about categorising knowledge into classes – cataloguing “god’s creation” not understanding how it evolved. It was only very latterly about “understanding the process” and never about “working practically” and so the core philosophy of science has always rejected the idea of “seeing how they work in practice” which is really what the mis-named “scientific method” actually does.

I am beginning to wonder if the idea that “the scientific method” is part of science, is a great modern myth taught to me at School and University. In retrospect, it is quite apparent that “science” started as a form of collecting facts with no testing at all in practice, that it would have continued like that if it had not been for the industrial revolution and the assimilation of ideas of theory and practice from engineering. And in many areas of academia, the testing requirements implicit in the so called (and probably misnamed) “scientific method” are not a feature of “science” at all.

I am now pretty sure that the so called “scientific method” was pinched from engineering, where the concept is so ingrained that it doesn’t even have a name. It is just the way engineers work. It is the philosophy at the heart of engineering just as “healing people” is the heart of medicine (or is that human-engineering?)

Therefore, the essential idea of science is not “the scientific method”, but one that the whole universe can be understood purely as a theoretical construct by “cutting up” the universe into smaller and smaller constituent parts and then reconstructing them according to “scientific” theory.

But that idea is not only impractical, but I hope to suggest it is also theoretically wrong. But first a ….

Practical Example

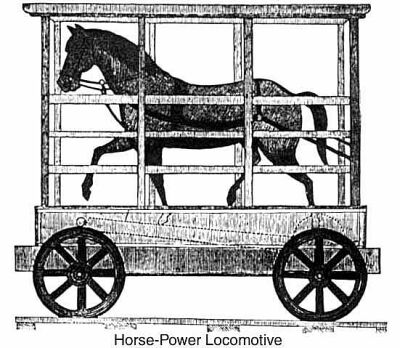

Let’s take a practical example (not that this example is actually practical). Below we have a horse powered vehicle, The vehicle is powered by the movement of the horse on a belt which then turns the wheels.

According to “science” this problem can be readily understood by looking at the various constituent parts, working out the various forces between these parts, etc. In essence this is what I call “deconstructionalism”: the philosophy that the whole is just the sum of the parts, and that be “cutting up” (latin: scindere), any problem can be broken down into constituent parts, each of which can be understood theoretically, and that the behaviour of the whole can be precisely predicted by knowing the constituent parts.

According to “science” this problem can be readily understood by looking at the various constituent parts, working out the various forces between these parts, etc. In essence this is what I call “deconstructionalism”: the philosophy that the whole is just the sum of the parts, and that be “cutting up” (latin: scindere), any problem can be broken down into constituent parts, each of which can be understood theoretically, and that the behaviour of the whole can be precisely predicted by knowing the constituent parts.

So let us assume the scientist does their “science”, works out the various forces and weights etc, and says “yes the carriage will work”.

But then we give the problem to an engineer who then says:

- You probably wouldn’t get this past the vehicle licensing people

- It would probably break animal cruelty laws

- It has no steering – or if it runs on rails, there’s a lot of railway legislation which undoubtedly needs a driver, lights etc.

- There’s no means to control speed or to cope with a “runaway” horse.

So, who is right? Is it the “scientist” who has just worked out that the carriage will move as theorised, or is it the engineer who says that there’s not a hope in hell of getting this contraption to work in the real world.

The difference between academic science and engineering science is not science

Notice, this problem would be a pretty trivial one for almost all engineers and likewise many scientists (although those who do genetics might struggle?), so the different response is not caused by any significant difference in skill applying the science/engineering of mechanics. Instead the real difference is focus: that any “scientist” would likely see this as a theoretical exercise in forces and not even consider the law, animal cruelty, the driver etc., whereas the engineer, who is just as capable on the science is trained to look at the problem holistically – or indeed “whole-istically” so that they also include practicalities including law, human-machine interface, etc.

And notice the key difference is that the engineer sees the problem “as a whole” whereas the sciences teach us to “scindere” or cut the problem up into constituent parts. The result is that the engineer isn’t led to focus on the easily “dissected parts” and instead, it is a natural part of the engineers work to consider far more complex issues:

- Human-machine interface

- Human psychology

- The law

- The practical experience of people with similar devices

- Insurance, legal liability, etc.

But science also deal with …

I remember my own attitude coming into engineering was that science had the answer to everything – you just had to apply it. As such, those believing in “science” will naturally look at the horse contraption and say “but science has all the answers because there is also … and then they will say “and there is animal psychology – which tells you how the horse behaves, transport science which deals with … and if you wanted to know about the law … there are academics who also deal with that.”

In other words, the response to the criticism that the scientist did not actually determine if “it would work” is to say that if only we had also asked perhaps a dozen or more academics and ask them to specifically look at each aspect of the horse carriage, that we might just get the same response as the engineer who said “it’s impractical”.

In other words …. one engineer is worth more than a dozen academics!!

To use another example, outwith traditional “science”, let us consider a patient with a shoulder pain. They have a choice:

- Go to their local University with its faculty of medicine

- Go to their local general practitioner.

According to the theory of “science knows best”, there is absolutely no question that the very best place to get advice is to go to the academics in the University.

However, even if that choice were available, we all know that academics are extremely limited in their general knowledge because what they know is focussed in one area. Therefore, each academic will try to see the problem in terms of their own specialism:

- Surgeons – will see a need for exploration surgery

- Psychologists – will see a need for psychological investigation

- Physiotherapists – will see this as a problem of the interplay of muscles joints etc.

However, if we go to our GP (i.e. human engineer), because they have undoubtedly seen a lot of other people with similar symptoms, they will probably ask: “do you have a desk job … and do you use the PC a lot”. If the answer is yes, then you will probably receive some advice about posture and adjusting seat heights, taking breaks etc.

And the GP’s advice is very likely to work, despite the fact the GP has no real idea what is causing the pain, nor have they investigated the psychology or physiology. They haven’t “cut up” the problem (and nor would we want them to) but they will more than likely resolve the problem than the academics because they have the experience of what works – and like engineers, a good knowledge of the relevant science.

The whole-istic approach works!

So, there are whole groups of people who look at problems using science (doctors, engineers) but who do not “cut up” the problem but deal with it “whole-istically”. As such they may guess at a “cause”, but the approach is focussed much more on what works based on experience and practical knowledge. This approach is often highly criticised by academics. In software engineering it is seen as “tinkering” and academics insist the “proper way” to look at a problem, is to break it down into the constituent parts, to separate these out into “procedures” or “objects”. “Proper” is seen as “cutting up” the problem. But in reality, few engineers could possibly “cut up” their problems, doctors can hardly diagnose simple muscle pain by “cutting up” their patients. Engineers, know that more problems tend to be introduced by taking apart systems – so again it is a last resort.

So why do academics have this view that problems must be “cut up” into constituent parts? The root cause appears to be an assumption that the whole world is best described as one part “causing” the behaviour of another. But this fails to take account of the fact that real world systems are far more complex and that such descriptions of “causation” only really work in simple systems which are neither too small (so quantum effects come in) nor too big (so that the system itself is too complex).

So, why this faith that “causality” can and must explain everything? Why “must” something have caused the 20th century warming? We take the advice of doctors who tell us to “take a rest” if we are under the weather or that a cold will “get better”. Obviously if it does not, we go back, but probably 99% of the time the doctor is right. But they never once knew the real “cause” of our illness, nor how the actual problem manifested, physiologically, psychologically, sociologically, metaphysically, but we take their advice and almost always get better. So if we can take this non-causal advice for ourselves, why are some people so overwhelmingly compelled to seek causation for a small rise the the planet’s temperature – when we don’t do anything similar for ourselves?

The origin of the sin of causality

It is a part of the Christian philosophy that there is something called “sin” and that it is because of this sin that god punishes us. And this I think is the origin of the philosophical idea of “causality” – and perhaps a reason why it is so enthusiastically endorsed by certain countries.

However, this idea wasn’t without its problems. Because just as now, the climate would turn, the people would die and the congregation would ask “what have we done to deserve this”. So, in order to keep the link between cause and effect, between “sin causing the evil in the world”, the academic-theologians invented something called “original sin”. That is to say, that everyone is born with sin, and this therefore justifies all the bad things that happen to us. But most people I know either don’t know or don’t care about such concepts as “original sin”.

These days it is very common to hear things like “shit happens”. That is to say, some things either cannot be explained.

Climate: shit happens versus “original sin”.

How often have you heard some climate extremist say: “something must have caused the [20th century] warming?” The argument flows thus:

- Something must have caused the warming

- You [sceptics] cannot explain it

- Therefore … you must accept the explanation they [climate extremists] give

- Therefore .., as they assert CO2 caused the warming … they think they have “proved” CO2 caused the 20th century warming.

This is really very similar to the argument re original sin:

- Something must have caused the evil in the world

- You [sinner] cannot explain it

- Therefore … you must accept the explanation they [high priests] give

- Therefore .., as they assert evil is caused by sin – everyone must have committed a sin even before they are born.

Now compare this with the sceptic approach

- There was warming in the 20th century

- Shit happens

To which the climate extremists then say:

- “but you must take this seriously”

- Sceptic: “I cannot see any trend at all suggesting there is any significant problem from the climate, but I can see massive problems economically if the world does what you suggest”.

The Theory of non-causality

The statement “shit happens” is a reflection of what happens in practice. But the question I now want to ask is whether causality may not only be impractical to discern in many cases, but that it may not be strictly true that there is causality at all in much of what happens in the universe.

There are various reasons to suppose this:

- Quantum mechanics imposes a non-causal philosophy on particles in the sense that the time and place at which an atomic interaction occurs cannot be predicted except in “overall” (whole-istic) terms.

- Chaos theory, shows that in many systems causality does not exist beyond a theoretical limit. In other words, theory cannot predict the outcome, so there is no practical causality.

- In complex systems such as the human body, society or the climate, the number and complexity of the system is such that no practical model of the system is possible that can model its behaviour entirely.

But when we combine all these, that because of quantum mechanics systems cannot be “cut up” into smaller and smaller blocks each more predictable than the whole, that because of chaos theory, whilst each atom may be small, the combined long term effect is chaotic, and that because complex systems are just too complex to model, it is not only practically impossible to know if they are predictable but it is … THEORETICALLY IMPOSSIBLE TO KNOW IF THEY ARE PREDICTABLE.

Therefore I propose the following:

That there are systems where actions occur without causation.

Natural variation

The practical implication of this concept is that “natural variation” is not just a term lumping things that have not yet been measured, but that natural variation is a manifestation of non-causality. That due to the combination of quantum mechanics, chaos theory and the shear complexity of the system we not only will never practically know what causes “natural variation”, but that we cannot theoretically know either.

In other words, when we deal with macro-complexity on a scale of the climate, we should not only see it as practically impossible to predict, but theoretically impossible to predict its behaviour except as a “whole-istic” sense that there is a scale of variation that tends to occur – without any reason.

One of the finest essays on science and engineering I have ever read. Thanks. I’ll be sharing this with my good science teacher friend tomorrow.

Bravo.

~Mark

Thanks – however my family brought me down to earth when I explained it and they said: “that is not new: everyone knows “shit happens”.

Also in many situations the whole concept of “cause” is meaningless because the problem is so multi-faceted. Take e.g. a blade of grass – what “caused it”? Yes we mow the lawn, but that does not explain why that one blade of grass happens to be there, or how it evolved. It’s so complex that “cause” is meaningless.

Well, S.S., as a Taoist I have always been down with “mutual arising” which is nearly the same thing as your “Theory of non-causality”. See here for a short essay on the concept and society.

https://markstoval.wordpress.com/2013/05/19/spontaneous-social-order-mutual-arising-and-the-tao-of-laissez-faire/

However, the best part and the part I was referring to was the beginning of the essay where you compared the academic “scientist” to the scientific engineer. I have now over 40 years of helping young people prepare to become engineers (as well as, God Help Me, lawyers and such) and it is the engineering mindset that moves society forward. And you can see it in children, sometimes from a very early age. It is almost as if some kids are genetically predisposed to thinking logically and skeptically.

I would love to see you take the time someday to do another post comparing things that “sound good on paper” but then fail in the real world. Perhaps using examples that would be easy to explain to teenagers who have not yet been off to university.

Anyway, great post. I appreciate you sharing.

~ Mark

Having come here via a comment you made on Bishop Hill’s site, I read this piece out of curiosity. In this matter, you speak for me.

As an old coot from a scroty background, I was probably among the last to get a decent state education (1960s/70s). It included an engineering degree and I still read physics & maths books for fun, trying to keep up to date with science and engineering.

When accused by religious zealots & climate disciples of being ‘sceptical’, I have responded by asking them for the antonym of their word ‘sceptical’. Mostly they struggle, so I suggest ‘gullible’ and then ask them which they’d rather be. The consequent spluttering never fails to amuse.

Your observations are right on the mark, but I despair for the future. Carl Sagan’s last book (“Science as a candle in the dark”) predicted a return to the dark ages & we seem to be right on track.