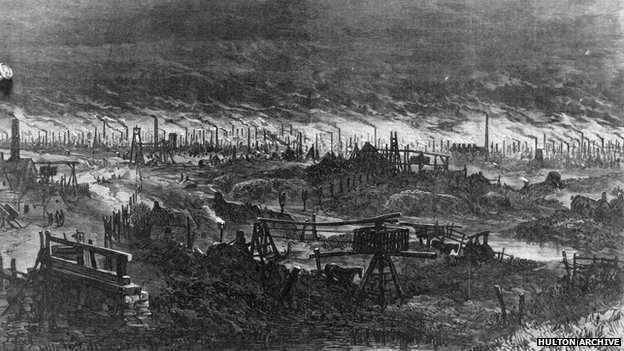

For all Tolkein’s good points, he like so many of his generation of public-sector academics shared a hatred of industry. And this is easy to see in his portrayal of “Mordor” above. Compare that to the typical portrayal of the Industry in the Blackcountry.

Now contrast that to the Idyllic setting of the “Shire”:-

The shire, the quintessential English countryside full of green grass and sheep and not a single industrial facility to be seen.

So where did all those consumer goods come from: plates, cups, knives, forks, clothes, wheat (flour), carts, horse bridels, books, timbers, gunpowder (fireworks)., etc. etc. etc.?

Clearly – like academics today, the shire is the recipient of vast amounts of manufactured goods, but there is no hint of where they come from. The truth is that the only industry seen in the world of Tolkein is that being done by the “forces of Mordor”. So, there appears to be only one source for these consumer goods! Are they, produced by the very orcs who are so loathed – there’s no other credible explanation.

It appears that almost all the goods in “middle earth” are produced by the “forces of Mordor”, in the same way academics today live off the consumer goods that they themselves purchase in abundance – but then loath those who produce them.

The truth about the Idyllic Countryside

Fig 23: From Theodor de Bry’s America 1590″A Werowan or great Lorde of Virginia” (detail) engraved by Theodor De Bry after a painting by John White.

Where does this hatred of industry come from? It stems from a false perception that the past was full of “noble savages” who inhabited a world very much like the shire (or spires of academia), where everything was green, there was none of the “horrors” of those Anglo Saxon “marauding” industrialists with their uncouth Anglo Saxon 4-letter words. Where no one speaks of a “Pause” but instead calls it “Hiatus”, where “Manmade” is “anthropogenomordorus”.

But this flies in the face of reality.

The real countryside was full of shit, of dirt, of disease. People lived with animals in their houses – Can you imagine what that was like in the winter? The rain would fall, the ground would turn to mud and this is what you get:

The photo above is what Tolkein’s shire would have really looked like. People would have been crowded together to protect what little they had. The communal areas would turn to mud, not just for a few days like Glastonbury, but for months on end. And faeces and rubbish and cattle shite and broken pots and sharp stones and bare feet would mix to ensure many children died. That’s the reality of the “Green” shire of academic dreams – BROWN THICK KILLING MUD!

And what was the reality of the satanic mills to which everyone flocked?

To the young aspiring living in the country the place to go and start a new life was these new industrial towns. The streets were cobbled, they were therefore clean. And so one could not only afford fine clothes, but the streets were clean enough to wear them:

The streets were cobbled, there was sanitation and relative to the mud “they were paved with gold”. Dresses could be worn without a tide line of mud.

For us, looking at the simple houses in New Lanark, it looks like poverty, but by the standards of the time this was luxury. Notice e.g. the absence of the cow! Notice how the floor is wooden and not cold wet mud!

And see the huge range of goods available to them! This is where all those items we see in the Mythical shire would have come from. Industrial goods produced in industrial sites like New Lanark, producing all the plates, knives, flour, cloth, etc. etc, which all that new wealth from industrialisation gave to all those people.

Their jobs were well paid so that they could afford the modern luxuries of the time, like clothes, fine foods (not just that they grew themselves).

Interesting article. I was just ruminating about this. I had looked up how to preserve the pounds of carrots my garden put forth this year and was reading a blog page on country life and how wonderful it was. To the author’s credit, she did note it was hard work. However, commenters seemed enthralled with the whole “country life” idea. Including, one supposes, mucking out horse stalls, cleaning chicken coops, pulling calves at 2 am. It never occurs to them that her life included a blog—a very modern, very social activity. Judging from the comments and other posts, this person also is on various social media sites. This is not “living the simple life” yet somehow people see it that way.

I have a cabin on the prairie. A neighbor there has a yard that looks like your picture of the UK mud. Her whole yard turns to mud. She spends hours patching her roof, keeping her solar and wind power going, planting trees only to have the critters eat them off, and she has an outhouse and no running water. She would trade this for a more modern home in an instant, though she’d still want to be outside of town. It’s not idyllic. That’s a fantasy.

Likewise, I used to watch the Biased Broadcasting Company program called the “GoodLife”. It was almost complete environmental propaganda – however, like so many other people, it really did look great.

But the reality dawned on me, when I realised that my own experience of “back to basic” life was during summers.

I’ve regularly been camping in the summer with around 80 other people. Several times, the rain has just poured and poured and the whole site turns to mud. It becomes impossible to dry clothes, food starts rotting in the packets because of the humidity and everything from tents to kid’s faces slowly gets caked in mud.

You can cope with that for a couple of weeks – not least by taking clothes to a laundrette and usually someone lives close enough to take the damp bedding away to dry in their house. But then I realised that before industrialisation, people would be living like that all the time. Winters would be continual damp, mud and no light.

The other things I didn’t mention is the smoke. I visited an iron-age house in Denmark. There was a layer of smoke from the ceiling down to about 4foot. That meant if you stood up, your eyes would start streaming – it was worse than any Pub.

They want to return to “Eden” – when that “Eden” was really hell on earth.

Hiya Scottishsceptic,

I am from the Black Country, and have read Tolkiens most well known books; Silmarillion, The Hobbit, LotR.

While I generally agree with the sentiment of your article, I would like to make this point.

What Tolkien hated about industry was the effect it had on the land, and the people living on it.

In 1841, the average age of death in the Dudley Parish was just 16 years and 7 months. An 1852 census concluded that Dudley was the most unhealthy place to live in Britain.

http://www.dudleynews.co.uk/news/13409508.Top_10_things_you_might_not_know_about_the_Black_Country/

I wholeheartedly agree with you, that country life is not the idyllic setting seen in Constable paintings. But the Blackcountry that Tolkien may have harked to, was the worst of both worlds.

The evidence is that people moved en masse from the countryside to the urban areas – that strongly suggests that the urban areas were better for these people, even if there were a few problem areas (which then get cited as if they apply generally).

Yes the huge attraction of industrial areas also brought problems – which as ever were solved by engineers – called sewerage. And infectious diseases were not explained by some university academic – however well intentioned like Tolkein – but by doctors working in the field. Indeed, the first doctor to work out the connection between infection and illness was I believe attacked by academics who then continued to kill 1000s if not millions by their teaching.

The single biggest attraction of towns and cities for the peasant was work. Work = food. For the poor, towns were very unhealthy on a long term basis but for the short term they could be the difference between starving or living.

The average age of death was deceptive because it includes masses of babies. There were two sources of significant death, the most obvious being disease. Water and air were both deadly at times. The close proximity of so many people made epidemics inevitable. The second source of death was one I only heard of recently and it was the change from wood fires to coal fires. Chimneys and fires that had coped perfectly well with wood, suddenly started emitting large quantities of carbon monoxide. Babies would have been so vulnerable to that. Add other poisons, lead, mercury, soot, etc.

So yes, in a way Tolkein was right, cities were terrible places and certainly in his era, we could have all lived the bucolic country life with hand looms, bespoke potters and even black smiths. However that can’t be sustained. It’s a highly inefficient use of resources including land. As populations grow, there isn’t enough land to sustain low yield farming. One of the things that The Good Life demonstrated was how much good quality land two people needed to survive.

And that brings us to the second reason why towns are essential – innovation. Towns allowed people with different skills to combine them, creating new technologies. It brought them new raw materials to play with, the most important being energy. Yes, people can subsist in the country but they civilise in towns. Even the pressures of living too close forced people to invent.

Would Tolkein have been a writer if he’d had to spend his days toiling in a field? Would he even have had much to write about if there had been no cities to be offended by? He wrote about magic doing amazing things but didn’t see the magic happening all around him that had nothing to do with elves or wizards.

The usual ploy used to denigrate the industrialists is to compare life in the early urban areas with life today. Instead the comparison must be between life in urban areas and life in rural areas of the same types of people.

However, what also happened is that people moved from the highlands to the lowlands, but kept their family in the highlands. But I read this in context of agricultural workers in the more prosperous lowlands.

My family tree reads like an economic migrant history book. Highlands, lowlands, Ireland, Devon, bit of viking and a blood group from somewhere in the middle east. Offshoots ended up in England, Canada, Australia and more. While my ancestors lived in some of the poorest communities they left relatively nice places (eg Irish villages) for worse ones (Lancashire mill towns) that had jobs. Mud is mud and cities had plenty. Sewage in the country is often easier to deal with than sewage in the city. Even now cities have problems with pollution that don’t exist in the countryside and people still flock to them for money and the better life that might mean.

The countryside is great if you have the money to enjoy it. Lots of money. But cities can offer things that individuals can’t afford by themselves. Theatre, museums, sports, libraries, etc. Early on they had the telephone, power, gas, shops. Only now that we have cheap, fast transportation can we enjoy the best of both worlds but those in the country can still miss out if they’re just too remore for decent broadband (ha, ha).

In Tokein’s era almost everything he wanted could be produced by hand but like hand crafted stuff today it was expensive. Industry not only produced things faster, it made them cheaper. That meant you didn’t have to be an Oxford academic to afford more than a cracked old plate and a bent spoon. Me, I love hand thrown pottery but I stick it on display, not eat my dinner off it. These days, many items cannot even be made in a micro business setting.

Industry is like the back end of a cow. It might be ugly, it might be smelly but the cow doesn’t function without it.